The tea ceremony arrived in Japan at the end of the 12th century. It was introduced by Eisai Zenji, a monk who went to southern China to follow the teachings of Chán Buddhism, which later became Japanese Zen. In China, for several centuries, tea had been considered a drink with remarkable properties, allowing monks to prolong their meditation practice.

So Eisai Zenji brought the meditative practices of Chán to Japan, founded the Rinzai school of Japanese Zen and enabled the tea ceremony to become more widespread. He assimilated knowledge of the procedures used in Chinese monasteries; he also brought tea plants and the objects used in the tea ceremony.

China was under the Song dynasty when Eisai went there. The way tea was drunk during the Song dynasty, notably in the Chán monasteries of southern China, was to steep tea leaves, crushed to a fine powder, in hot water. This way of preparing tea allows certain substances to be dispersed in the water, but also produces the taste of the leaf itself, the powder itself. It’s this combination that one tastes when one drinks a bowl of matcha—literally “rubbed tea”—prepared during the tea ceremony.

Following the Song period, China experienced a troubled period with the Mongol conquests. The Mongols founded the Yuan dynasty and largely eradicated Song culture. The Mongol dynasty was then replaced with a new Chinese dynasty, the Ming dynasty. Under this new dynasty, tea was produced by infusing tea leaves, which were therefore not consumed. Since the West came into contact with China during this period, the tea we have become used to, and which everyone knows, is leaf infusion.

The tea ceremony using matcha therefore almost entirely disappeared from China but continued to expand in Japan. It played an essential role there—socially, culturally, politically and spiritually—particularly during the long period of civil war that Japan experienced between 1467 and 1600.

In China, the tea ceremony originated from many spiritual influences, mainly Buddhist of course, but also Taoist and Confucianist.

In Japan, this process was further elaborated under the influence of the local animistic religion, Shinto. Thus, before entering a tea house, the guest will wash their hands and rinse their mouth as a sign of purification, just like any person entering a Shinto sanctuary.

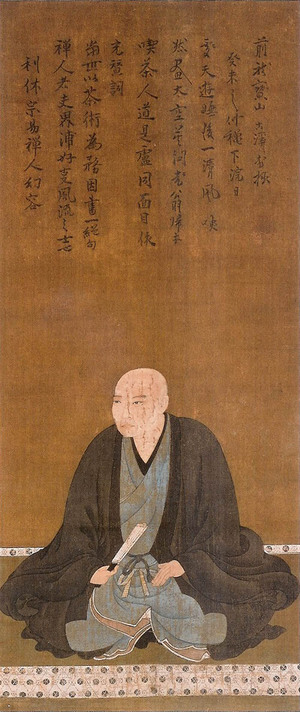

Christianity, which was prevalent in Japan during the 16th century, also had an impact on the tea ceremony, though historians are still debating the extent of this influence. Sen no Rikyū, the great tea master of the end of the 16th century, may very well have been Christian himself. It’s possible that certain procedures of the tea ceremony codified by Sen no Rikyū, such as the cleaning of the bowl, were inspired by the Christian Eucharist.

The tea ceremony has therefore spanned several centuries, evolving progressively; thereby reflecting the slow pace that characterises the ceremony itself and integrating influences from many spiritual traditions. Beyond its outward appearance of a traditional Japanese cultural practice, these multiple spiritual influences bestow it with a universality that one discovers gradually as one practises it.

The original French version of this article, written by Franck Armand, is published in the Revue du Centre Zen Number 70 (annual printed newsletter available in French only).